How Great Art Emerges from Moments of Lucidity, Not Madness

figure. The Scream

figure. Alexander Grothendiek in 1965

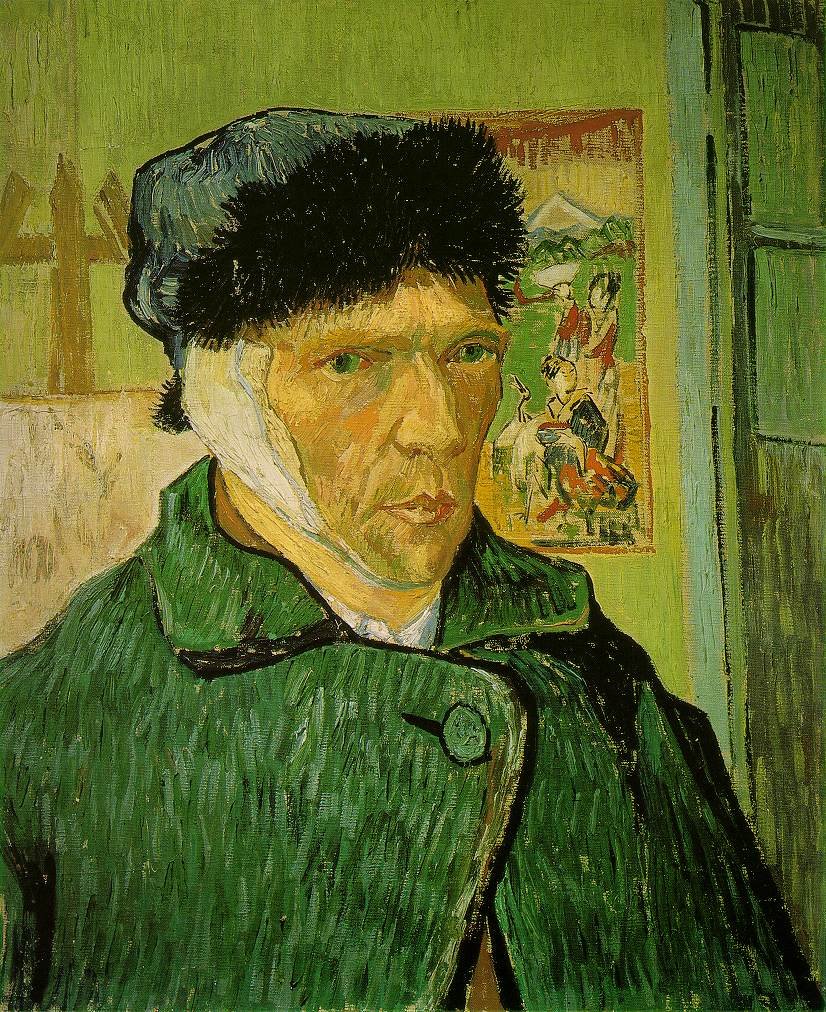

Van Gogh: The Battle Between Brilliance and Breakdown

Vincent van Gogh’s life serves as a meaningful case study of how creativity is correlated with mental well-being since his life was full of mental breakdowns and drastic fluctuations in creativity. The emotional journey when he simultaneously made the most precious artwork in life demonstrates the intricate links between creativity and mental health while fighting against his inner demons, which is clear from his more than 500 letters to his brother Theo. What is found in these letters is not chaotic ramblings, but a clear reflection on art, nature, and his own emotional fluctuations. They challenge the overly simplified idea of the “mad artist.”

A popular misunderstanding holds that Gogh sourced inspiration for his outstanding work from mental torture, as if suffering can arouse inspiration. Modern research presents contrasting points, suggesting that the vibrant sunflower series and “Starry Night,” among other representative works, were actually created in times of emotional stability. When he maintained clarity at the asylum in Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh spent much time painting, in a way that he described himself as “a locomotive that cannot stop.” By contrast, he was unable to produce any painting when suffering from potential epilepsy or bipolar disorder. It should be noted that during this time, he couldn’t “even hold a brush.” The ear-cutting incident did not occur due to a burst of inspiration; rather, it signified a disruption in his ability to produce art.

This model fundamentally challenges the romanticization of mental illness, positing that it invigorates perspectives through creativity. The talents of Van Gogh originated in clear moments during illness intervals, not the illness itself. His creative achievement was not a product of frenzy, but resilience and dedication shown by his persistence in creation despite serious mental issues, an effort showing. Van Gogh himself remained aware of such a difference, as shown by his letter to Theo: “The more I am spent, ill, a broken pitcher, by so much more am I an artist…though it is a melancholy consolation.”

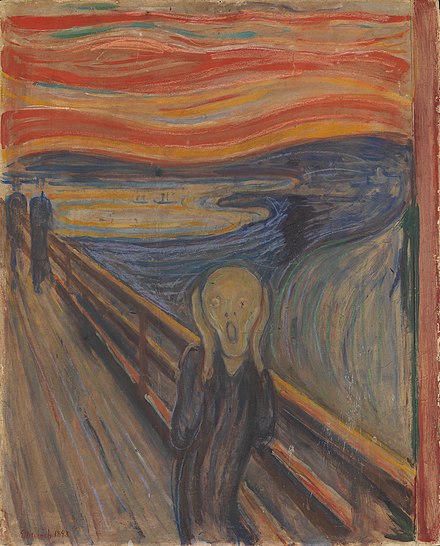

Munch: Channeling Trauma Through Deliberate Artistic Control

The unique life and work of Edvard Munch offer thought-provoking insights into the relationship between mental torture and creative expression. Munch’s relationship with strategy began when he was a child, with the loss of his mother at age five and sister Sophie at 14. These traumas weigh on his life and art, such as “The Scream,” where distorted perspective and blood-red sky arouse a survival-related terror that resonates for generations.

Despite struggles with alcoholism and mental illness, Edvard Munch exercised control over his creative choices and professional growth. His seemingly chaotic and distorted paintings, like elongated figures and twisted landscapes, were conscious artistic decision-making instead of uncontrolled reflection of psychosis. Munch himself made this difference highly clear in his statement, “I paint memories, not reality,” indicating his conscious transformation of emotional experience into visual form. This approach is a powerful challenge to the stereotype of the artist compelled by the frenzy that is out of control.

What proved to be most striking was the business acumen exhibited by Munch. To illustrate, he meticulously managed exhibits and sales since he engaged in this work. He demonstrated an extraordinary capacity to transform internal torture into artistic work with substantial market value. his resilience and professional intelligence. When Munch engaged in creation, he was actually exploring his inner world in a controllable manner. In this process, artistic innovation. As noted by Munch, “Disease, insanity, and death were the dark angels standing guard at my cradle, and they have followed me throughout my life.” However, these dark angels did not overwhelm Munch, who managed to control them through disciplined artistic practice. In this process, a visual language came into being, and now, it tells a story of universal anguish shared by humanity.

From Freudian Theory to Modern Neuroscience: The Scientific Evolution

The public began to systematically explore the correlation between creativity and mental anguish at the dawn of the 20th century. As proposed by Sigmund Freud in the 1920s, artistic creation was out of sublimated inner conflicts, which means the transformation of unresolved mental tensions into cultural products. This viewpoint swayed how artists engaged in reflection in the decade to come. For instance, the work by Van Gogh and Munch was believed to be their attempt to resolve their internal conflicts with unconsciousness. Although this theory serves as a necessary framework by which artistic creation is interpreted, to some degree, it still romanticizes mental torture in an implicit way, as if suffering is the prerequisite of artistic success.

As rigorous research arose in the 1960s and 1970s, a significant change took place in this field. Psychologists came to analyze how creativity and mental well-being are correlated through empirical investigations, a move that transcends previous theoretical assumptions and anecdotal evidence. Groundbreaking work by Kay Redfield Jamison and others sheds light on the fact that some mental conditions, such as bipolar disorder, are statistically correlated with creative success. It should be noted that these findings should be rigorously treated.

After the 1980s, the academic field has become increasingly aware of the oversimplification of the “mad genius” as a stereotype, finding that sometimes, it brings about negative influence. According to the current mainstream viewpoint, different mental conditions have diverse but intricate influences on creation. Specific aspects of some mental conditions indeed can strengthen creativity. For instance, associative thinking occasionally occurs from bipolar disorder. However, these conditions may pose enduring hindrances to creation. According to modern neuroscience, creativity is a result of the coordination among multiple brain networks, instead of an isolated sense of “madness” or “inspiration.”

figure. Sigmund Freud